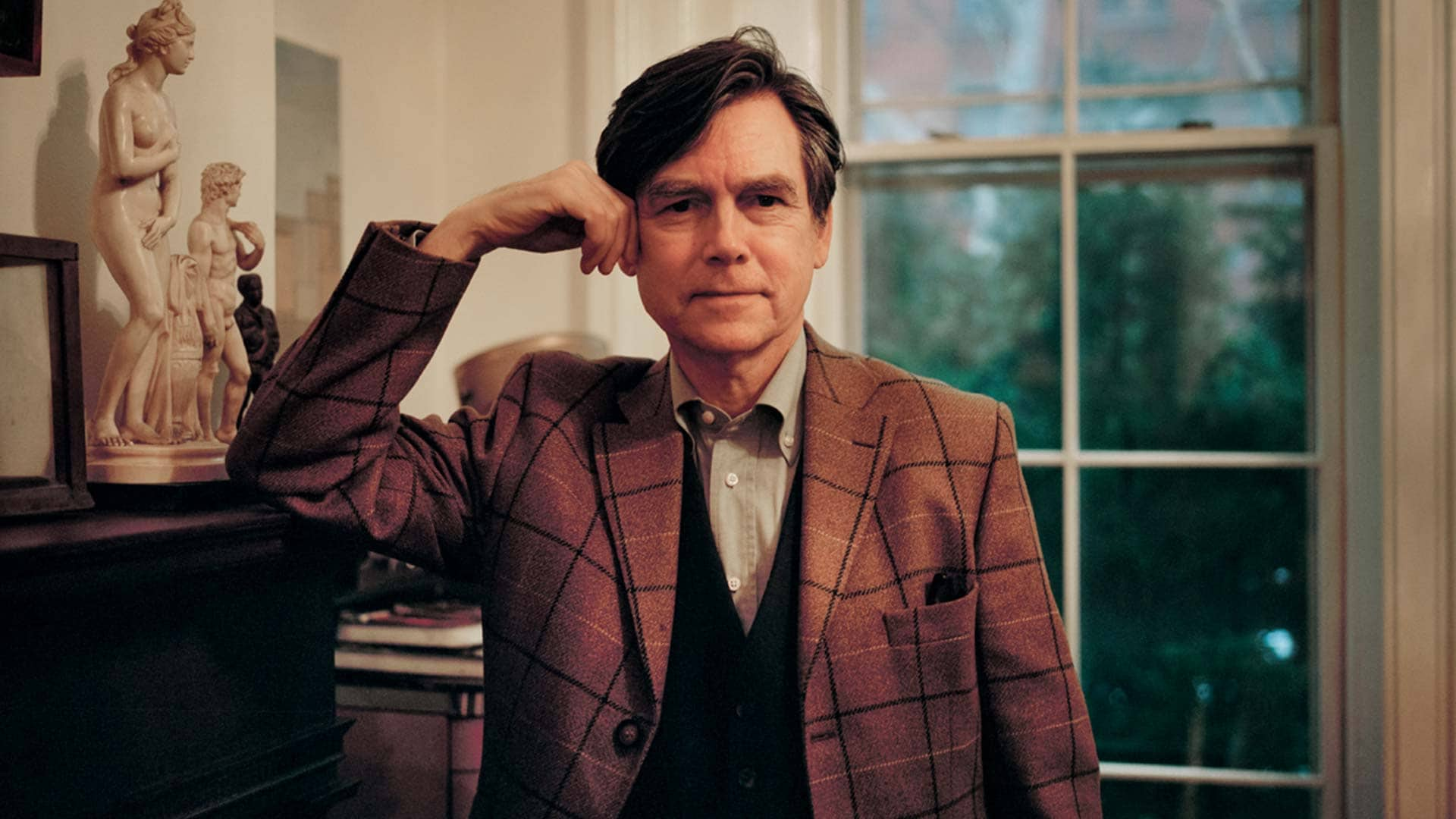

Antón Arrufat, the Cuban author of more than thirty novels, plays, and volumes of poetry and essays and stories, once tweaked a declaration of Sartre’s: “I was not born surrounded by books,” Arrufat writes, “but I will die surrounded by them.” The intervening period has, to be sure, proved sufficiently bookish. When early in the course of his long career Arrufat drew the condemnation of the post-revolutionary government, he avoided prison but was consigned to a provincial library on the outskirts of Havana, where he was once blamed for someone else’s crime of masturbating onto a student copy of a female nude by Goya. (Arrufat, whose punishment was to clean the library for six months, is gay.) Unlike other major Cuban writers following the revolution, however, Arrufat never went into foreign exile, and after a long chill the government relented, embraced him, and in 2000 awarded him the nation’s highest literary honor. His 1968 play Los siete contra Tebas (The Seven Against Thebes), which first led to his political ostracism, was finally performed in 2007, and his work—persistently concerned with the color and feel of Havana’s streets and the subtle abidance of the fantastic within the mundane—entered the Cuban canon, though surprisingly little has made it into translation. This public rehabilitation is visible as well in the palatial salon-cum-residence to which he was recently assigned, just off the Prado, where he welcomed us one January day. (I had come with two translators, one Cuban, one American.) Waving from a balcony amid the bougainvillea, Arrufat seemed especially spritely—for a man past eighty—when only moments later he unlatched the downstairs door for us. But when we went inside, the foyer was empty. A fishing line snaking down through a network of pipes had pulled aside the latch. Upstairs, we settled into an airy sitting room with tapioca walls and big shuttered windows through which poured the sounds of the Prado, the delicate antique furniture and book-filled vitrines too sparse to mute the putter and roar. Arrufat has written that youth and senescence are the ages ideally suited, respectively, for reading and “the supreme art of rereading,” so we thought to ask him which books from the first age he was encountering in the other. (He was indeed, for the record, young beyond his years as he lounged angularly, sweatless, in a white shirt and loose trousers.) * * * “My mother gave me a book parents always give their kids,” he says, “the novel Heart, by Edmondo de Amicis. It’s a book I like a lot, and that fifty years later I read again. It continues to interest and delight me, because it’s one of those books that’s mixed with one’s life. It’s mixed with my life in Santiago de Cuba and with my education, and that’s why I went back to it. The author has no literary importance. The book is important because it’s for boys. “Books that you like, you keep liking. And the books you like,” he explains, “sometimes can’t be defended—there’s nothing to discuss. One doesn’t always remember good books, one sometimes remembers minor ones. There’s a nineteenth-century French writer, almost unknown, named Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, and I like him a lot. I don’t know why. Tastes can’t be explained all that well. A friend of mine said, ‘You’re an old-fashioned person. Instead of reading Paul Auster you turn to Barbey d’Aurevilly, whom no one reads.’ Right now I’m reading Barbey d’Aurevilly.” Arrufat says he’s never been able to get back into Zane Grey and the other American cowboy novels he read as a boy in Santiago de Cuba. Then he thinks of Robert Louis Stevenson. (Borges once enumerated different sorts of just men, the antepenultimate in his list being “He who is grateful for the existence of Stevenson.”) “I like Stevenson more than before,” says Arrufat. “I’ve discovered many things in him that I’d never noticed as a boy, and I realized that he’s not an author for boys—that’s a publisher’s invention. “I was twenty-five when I first read The Great Gatsby, and it struck me as extraordinary. Recently a Spanish journalist for El País asked me to write something on it, so I went back to it. And it impassioned me and I found many things no one had noticed. It’s a work of mysterious erotic complexity. And there’s this personage living in this house with this pool receiving all these people who look in the library for the book that has the name of God; this type of thing seemed to me really extraordinary.” Following our meeting with Arrufat, the American translator and I read and reread the relevant part of Gatsby, vainly looking for any hint of such a book, and conclude that Arrufat—like the owl-eyed genius loci of Gatsby’s library—had seen something to which others are blind. Arrufat lived in a New York nearer to Fitzgerald’s than to today’s, between 1957 and 1959, and there and then, he says, “I spoke English. With time I have forgotten it. I worked in a bookstore. It was in the Village, on 14th Street, and it sold course books to Columbia University. The owner was Italian; he became a millionaire and bought a mansion in Jersey.” What else is still vivid from that time? “I ate a lot of hamburgers, they were very cheap.” “Before I went to New York, in 1957,” he goes on, “I had a library here, but it disappeared, and that pleases me because on that ship were many books that I was never going to read, which were part of the library. And I liked that they were lost. There are many books one bought to read, and then time passes and one doesn’t read them. “These days I never read lying down, because I’ll fall asleep within five minutes. It can be the most impassioning book in the world, it can be Proust, and I’ll still fall asleep. I always read seated; I used to read standing up because priests would read walking. They’d read the breviary and the Bible that way. “Speaking of Proust, I just finished reading Rubén Gallo’s Los Latinoamericanos de Proust. Gallo discovered a group of Latin Americans who were friends of Proust’s. A Cuban, de Heredia; an Argentine, Yturri; a Venezuelan, a musician who became famous in Paris; and a Mexican named Ramon Fernandez. De Heredia was the first Latin American to enter the Academie Française, which was very impressive, because to enter the academy you have to speak French with perfect pronunciation. The French speak the worst English, the worst Italian, but they can’t stand when French is spoken poorly.” What, we ask, did Proust know of Cuba? “Nothing.” There is a silence. Then Arrufat adds, “About Mexico, he knew a lot. When his family died, Proust inherited a good deal of money, and he called a banker and told him he wanted to invest in Mexico. And he invested his money in what? In Mexican streetcars. Trams were constructed with Proust’s money. What an incredible thing: a writer gets into investing in streetcars.” We begin to ask about other books of his, specifically books we spotted when, in advance of our visit, we pored over the rich large-format photograph that the artist Andrew Moore made of Arrufat’s bookcase in his run-down former lodgings, before the move to the new apartment. What about, for example, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, the subtly subversive early-Soviet utopia-dystopia? Arrufat doesn’t remember it, but when we describe the plot in an attempt to jog his memory, he admits it sounds rather interesting—perhaps it is one of the intended but never-read. Ulysses? “I’ve always looked at Ulysses from afar,” he says. “One day I got closer, I felt I had to read it, and I read it and it managed to excite me, though not as much as another work of Joyce’s that I greatly prefer, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” Dickens? He sighs. “I’ve read a lot of Dickens. I read so much Dickens last year that I don’t even know what to say.”

Cart

Size

Quantity

Shipping to the United States.

Apple Pay is now available as a payment option.

Subtotal (Tax Excl.)