You use ‘freedom dreaming’ as a tool in your artistic practice and daily life. Can you explain what it means to you?

To me, freedom dreaming is about feeling your way into the world you want to live in even before it fully exists. It starts with sensation. The smell of jasmine on a night walk. The warmth of sun on your skin while floating in saltwater. A friend’s voice cracking into laughter. These moments become portals.

Freedom dreaming is what happens when you look at what isn’t working—violence, dispossession, despair—and instead of shutting down, you soften into vision. You imagine a world made of safety, abundance, and delight. In my practice, that means making work that feels like a hand held out. That says: this could be yours, too.

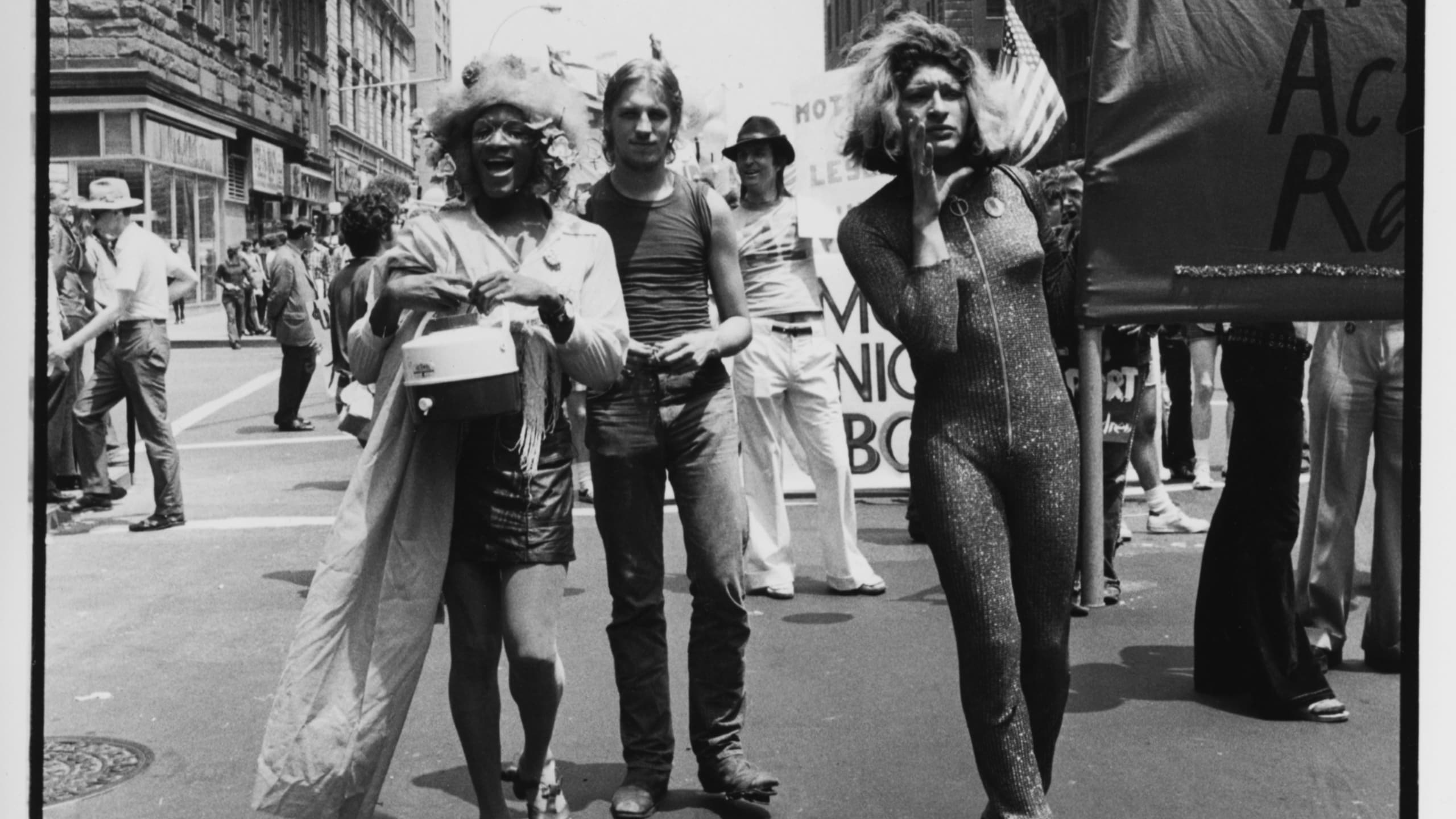

Was there anything that surprised you about Marsha’s story, in the process of writing this biography?

Yes: how much tenderness was there. The archival fragments, the interviews, the way people remembered her. It was full of softness, generosity, humour. Marsha wasn’t just fighting; she was caring. She was showing up to the hospital to check on friends. Giving her last dollar for someone else’s lunch. Spending hours styling flowers into her hair just because it felt good. I’d always known her as radiant, but writing the book let me see how layered that radiance was. It wasn’t just glitter—it was grit, it was care work, it was love braided into the hardest days.

Marsha P. Johnson is most well-known for her role in the Stonewall Inn riots. But what else would you like people to remember her for?

I want people to remember the way she made joy a practice. Not a luxury—an urgent necessity.

She was funny, glamorous, deeply spiritual. She believed in God and the saints. She danced at the piers and threw shade on Christopher Street and visited friends in jail and in psych wards.

Marsha’s life reminds us that the work of liberation isn’t just about protest; it’s also about sparkle, about softness, about staying alive and helping others stay alive, too. Stonewall was one night. Marsha’s dreaming was every day.

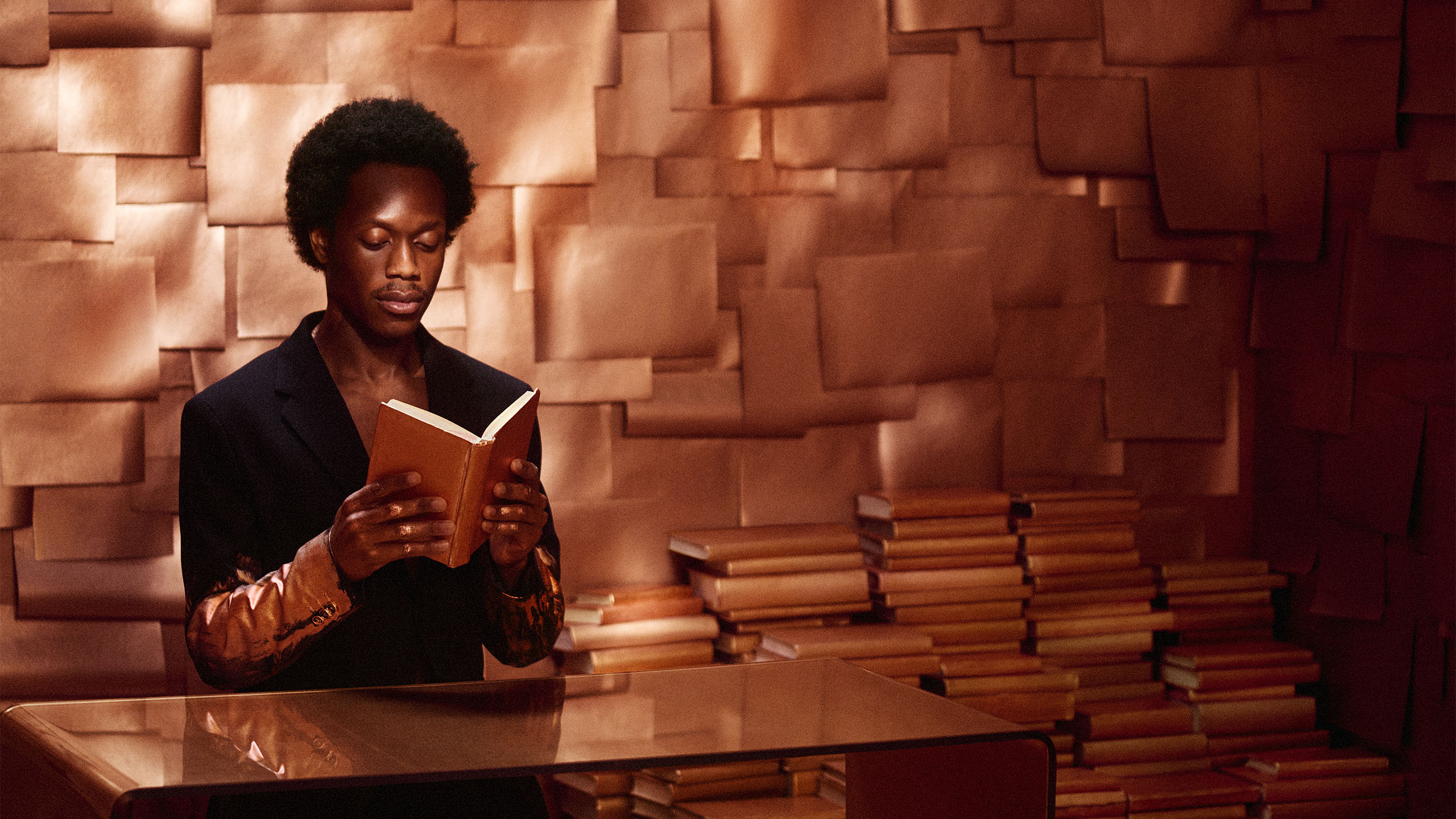

How has queer literature shaped your work—and whose work do you turn to for inspiration?

Queer literature saved me. It taught me how to see myself beyond survival. I think of Samuel R. Delany’s Heavenly Breakfast, the way he writes about touch, communal living, memory. I read it before I started filmmaking Happy Birthday, Marsha! and wanted to incorporate the intimate connections he illuminates into the film. I think of The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions, and how it reminds me that we can build pleasure even in collapse. Larry Mitchell the author was a friend of Marsha’s and Ned Asta the illustrator performed with Marsha in the Hot Peaches off-off-Broadway troupe. I think of Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ entire body of work. Janet Mock’s writing unlocked huge parts of me.

Lately, I return again and again to June Jordan—her clarity, her willingness to name beauty as urgent. I gave the commencement address at Hampshire College years ago and read her poems as a call to commence our full aliveness. These writers don’t just describe a different world—they make it, sentence by sentence. That’s what I want my work to do, too.