The tools Lenka Clayton uses to make her Typewriter Drawings are straightforward: a typewriter, ink ribbons, paper. The resulting pieces, however, each labeled with a typed title and date, range from simple doodles to intricate sketches. Some are narrative, with titles such as Amateur Drywall Installation, Marks on the Table from the Breadknife, and A Terrible Mistake, while others, such as a rhythmic repetition of parentheses that becomes an undulating seascape, are surprisingly beautiful. These drawings are atypical of Clayton's oeuvre, in that one can easily imagine how they were produced and how they might be displayed in a gallery or museum. But they also embody several threads that run through her artistic practice. They propose a counterintuitive use of an object not usually thought of as an artist's tool, with delightful results. With their inscribed dates—the earliest are from 2012—they have a diaristic feeling. And, most importantly, they showcase Clayton's inventive idiosyncrasy, her ability to defamiliarize the mundane. Clayton was born in 1977 in Cornwall, England, and studied documentary filmmaking at Central Saint Martins in London. She spent a few years in Berlin and then, in 2009, moved to Pittsburgh, where she still lives and works. Clayton seems at home in multiple media: ink on paper, photography, video, fabric. Her pieces are humanistic, poetic, and often tongue-in-cheek funny. Several play with the expectations imposed on her by family life: after the birth of her son, Otto, Clayton created the self-directed An Artist Residency in Motherhood (2012–15), a title she assigned to the practice of making art while also learning how to be a parent. She chose a location for the residency (her house), printed business cards, and set defined start and end dates. Her most recent work, a collaboration with the artist Jon Rubin, took place at the 57th Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, an art exhibition that dates to 1896. Their project Fruit and Other Things (2018–19) was based on a list of artworks rejected from the International in its first four decades: their titles were hand-lettered onto more than ten thousand paper signs and installed around the ground-floor gallery of the Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh. Each sign was displayed for only a day, and visitors were allowed to take home those which had already been shown—Clayton likes to imagine that the show created ten thousand new art collectors. Not long ago, I visited Clayton at her home in the Friendship neighborhood of Pittsburgh. It was a cool, overcast Sunday afternoon, and she offered me tea when I arrived. Once it was ready, we sat on the sofa at the far end of her plant-filled living room. Colored pencils and toys littered the floor, underscoring the quietness of an afternoon without her children—they were with their father that weekend. On the coffee table was a recently completed Typewriter Drawing of a hundred-dollar bill: it was a commission, by Otto, for his birthday. "He's a typical artist's child," Clayton said, "so he's super interested in money and how to make a living." **

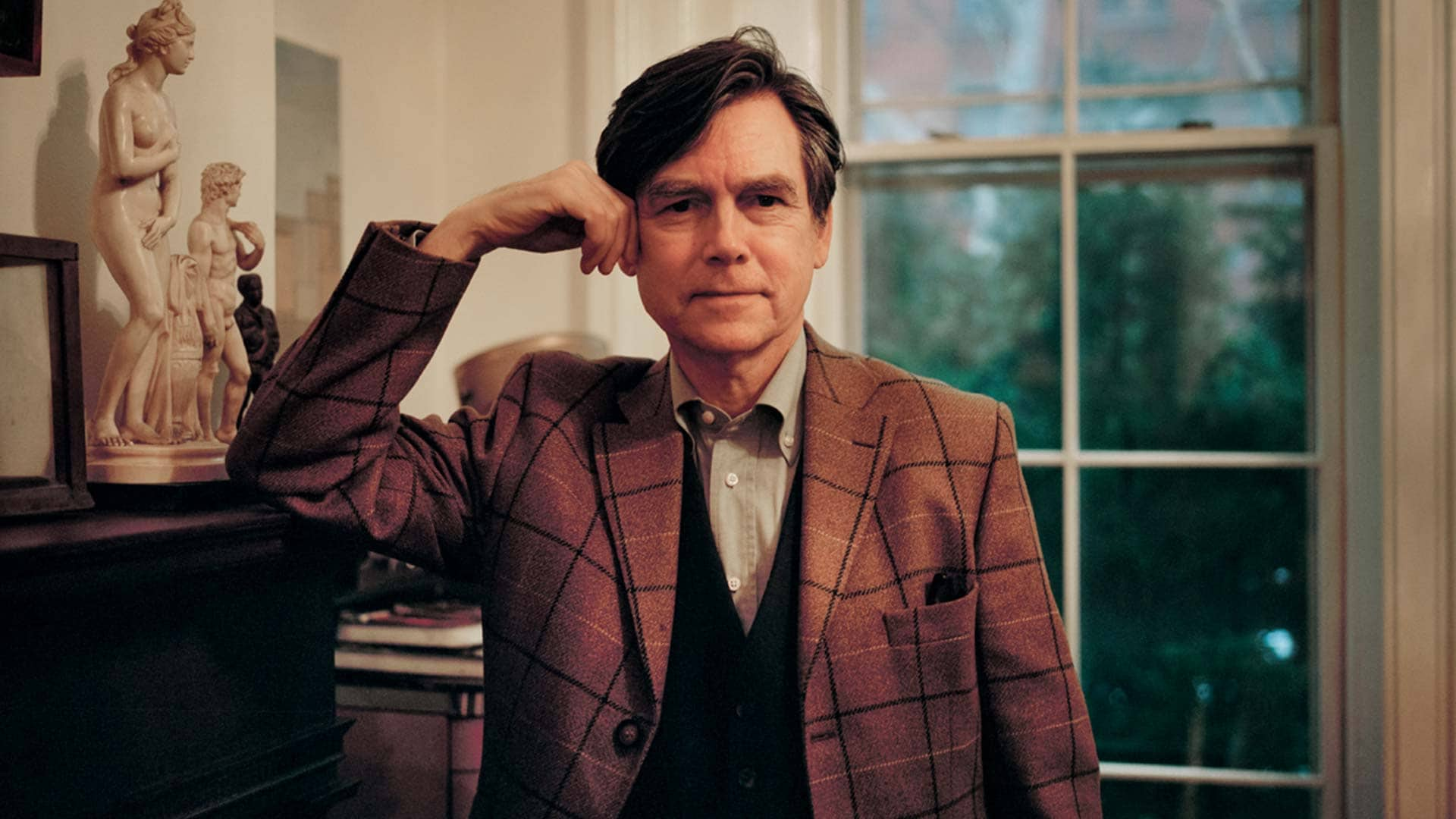

Lenka Clayton

Tell me how the Typewriter Drawings got started. I did a project called Mysterious Letters with Michael Crowe: we used the typewriter to write short, friendly letters to people all around the world. So the typewriter was around in the studio. And then Michael and I decided that we would do typewriter drawings using the typewriter. We thought we'd invented it. Obviously we hadn't, but we didn't know that.

Often I make art as a way of staying in touch with friends. I'm bad at staying in touch with people, but I'm good at doing the art projects that I say that I'm going to do, so Michael and I, we did a typewriter drawing once a day for all of November. And then we really loved doing it, so we did it for the next three years. And then I just didn't stop.

The typewriter is this wonderful limitation because it's really, really shit at drawing. It's just all lines and it's oily and... heavy. It's the opposite of figure drawing or something expressive. I liked that I had to struggle. At first I'd draw really simple things, like a staple, and it would take so much work, figuring out to draw that staple. And that dance between me and the machine appealed to me.

You just had a big solo show in San Francisco, at Catharine Clark Gallery, with new Typewriter Drawings and a video called A Rock and a Stone.

Yes, the video was one I made with Phillip [Andrew Lewis], my husband. We were living apart for several months, and we each had a round stone with us. They were similar but different stones. We decided we would do this exchange as a way of continuing to work: we'd have this stone and we would do something with it, like smash a glass or roll it down the stairs and video it and text it to the other person, and then they would respond with their stone in their environment. It's a hundred back-and-forth videos. It was a situation that was in life that then we made this frame around—

As a way to stay in touch?

Yes, but I also began to think about this distance, this not being together, as being a useful material rather than a reason to not work. Not sharing space gives us a chance to use that energy. That's a powerful idea: difficulty or inconvenience as material. Is this something you've taught your students at Saint Martins or Carnegie Mellon? Limitations are really important for me. A lot of people feel, especially when they're younger and haven't had a bunch of different experiences, that arriving to a place from where anything's possible is an important aim, and I think the opposite is a much easier place to work from. Often my students would have incredible ideas and they'd make work that is about that idea rather than out of the idea. They'll make a work about, I don't know, disintegration, rather than allowing something to disintegrate. It's a small shift, but it's really dramatic to move from an illustrative plane to using the entirety of a situation as something that you can potentially work with. Your projects often engage the public directly. Do you consider yourself an artist with a social practice?

I think of myself as an interdisciplinary artist. The way that I work is incredibly clear to me, and consistent. I developed work the same way when I was fifteen years old as I do now. The medium is often different, but that to me is not the most important part of a practice. A lot of students ask me how it's possible that I can work in so many media, because it's taught that it's more difficult to be successful, which is nonsense. My material is the world around me and my experiences within it, and so I'm always working or thinking or paying attention, and then that shows up in my work. It's all the same practice of living and being and making work. With the Artist Residency in Motherhood, it was important politically to me to work as an artist who has children and not deny one or the other in order to fit more comfortably in a certain box. You hear things like, "Oh, it's more professional to not talk about your kids if you have a gallery meeting." There's an idea of professionalism that negates life. I completely reject that. On the back of the business cards you made for the Residency in Motherhood, you listed a time frame— Yeah, 227 days. How does that work? Are you not still "in" that residency? No, it had to have an end. In order to be on, I also have to know when I'm off. So having a limited period to be in residence meant that I made the most of it, and it meant that it was finite, and it meant that I could fully invest in it without thinking, "What else should I be doing?" It was a way to completely engage with it. Did you feel a feminist responsibility in creating that work? "Responsibility" is a massive word, but yes, I definitely felt it. When I told people about the residency, some men said to me, "Oh, you had kids and now you're making work about kids? Oh, cute." Incredibly patronizing stuff. People also told me, "Well, you're going to be pigeonholed if you make work that acknowledges motherhood." That's crushing. Yeah, it's ignorant and incorrect. I continue to feel a responsibility to be an artist and to be a mother and to openly share that. There are more than eight hundred people in fifty-six countries undertaking an Artist Residency in Motherhood now. It's absolutely mind-boggling to me. How did Fruit and Other Things come about? Jon [Rubin] and I came across the list of rejected artworks quite early on, and we knew that it was going to be the core of the project. The majority of the research time was thinking how to make a structure where that list got to have the main stage and we got out of the way. There were a thousand decisions. The one thing that was really surprising was, we built this giveaway table, and we imagined that the paintings would sort of stack up in there and then people would come, like in a record shop, and leaf through them and choose the one that spoke to them. But they always got snapped them up quickly, so there were barely ever any paintings on it, and people lined up to claim one. We couldn't have imagined that.

Sometimes it was like three hours long, so it was this huge sort of human sculpture that became one of the main elements of the piece. We spent a long time thinking about the materials for these paintings. We chose paper that was a little bit too big to be comfortably portable, so you'd take extra care of it. And it was stiff, so you couldn't scrunch it up and put it in a trash can. We had the certificate of authenticity so it would be clear that each one was unique. We took all these pains to imbue it with this essence of being a work of art so that people would take care of it, but until it began, until the first day, we really didn't know if it would work or not. All these works got a new life, of sorts. They got into the show in the end, because they were rejected from that exact show, but there was just a one-hundred-year delay.That was one of the amazing things about working with an exhibition with such a long history. The works themselves operated almost like poetry: boiling down something to its essence—its title, in this case. Would you say that's a common approach in your work? I think that's right: boiling something down to its essence. I studied documentary filmmaking, and I think about editing all the time. My idea of a documentary is being present somewhere and collecting material from that experience, and then taking most of it away and allowing the remaining pieces to sit in juxtapositions that would never naturally occur in the world. And sometimes what you take away is time, so that in Fruit and Other Things, for example, moments from 1903 butt right up against moments from 2019 in ways that wouldn't normally be possible. How do your collaborations with other artists affect your work? Well, they're all different. They're usually relationships that already existed: for example, I collaborated with Nina Katchadourian recently. We have the same gallery; I'd met her, but I didn't really know her personally. I'd admired her work for a really long time, and we had a lot of crossover interests. Otherwise I collaborate with my husband a lot, and Jon [Rubin]. The collaboration with Jon... We've been friends since I arrived in Pittsburgh, and I knew of his work before I met him. When I was doing the Residency in Motherhood, I asked him to be my mentor, and he said, "Only if you'll be my mentor." So we had this nice co-mentoring relationship. And then he was one of the people who were being considered to put together a project for the Guggenheim Museum. This became ... circle through New York? Yeah, he proposed a couple of ideas and invited me to see if we could come up with something together, and we came up with ... circle through New York, which they chose. So it was sort of a respect-plus-friendship-plus-opportunity-equals-collaboration situation. When I work alone I tend to have very fast ideas, or rather, I wait until I have a very fast idea and then I'll make the thing, but working in collaboration is really different. You have to work together to create a joint, shared world.

With … circle through New York, we knew what we wanted to do. The brief from the Guggenheim was that we would work with communities that the museum wasn't usually able to reach. And we were interested in doing that, but we also wanted to implicate the power of the museum and think about how to redistribute it. There was all sorts of language in the Guggenheim's brief about what artists can do to create change and how that change can be permanent or sustainable and so on. That was something that we discussed a lot, because for Jon and me, that's not why we make work. What do you remember most from the experience? You worked in six locations in New York—including a pet store, a church, and a Punjabi TV station—describing an imaginary circle through the city. It's really hard to talk about that project because it was so dense: there were thirty-six different things that happened over six months, six times six. There were some really incredible moments, like The Oldest Song in the World. We worked with a musician and scholar from Barcelona who came over before the project started and traveled around the circle, teaching the song to everybody. It was extraordinary to observe: just imagine this song, which is 3,400 years old, being taught by this one person from Barcelona to all these different people. When it was at the Guggenheim it was sung by the administrative staff. They normally sit in offices on their computers all day, but they learned the song and then came out at 12 and 2 p.m. every day to sing it, like a human cuckoo clock. They would sing it into the rotunda and then get a standing ovation from people who accidentally heard it. You also played with the idea of the institutional power of the museum in your Unanswered Letter project. You found a letter in the archive of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: a man asked why his uncle's egg sculpture didn't merit the same treatment as an egg by the sculptor Brancusi. You sent the letter—more than forty years later—to museum curators around the world and asked for their responses. I was working on a project called Sculptures for the Blind, and in planning that I went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art and found the letter from Brian Morgan, which was written in 1974. It was the only personal thing I found in the archives. What were you looking for? I don't know exactly. The Brancusi Sculpture for the Blind was in their collection, and I was trying to find a direction to go with it. I was looking at that artwork. I had decided to begin with an existing work of art and find a prompt that presented itself. I was looking at everything I could find out about that sculpture. I found the letter, and it jumped out at me immediately. It was so beautifully written, and it's a question that we're not really allowed to ask. As soon as you leave art school, that's the end of "Why is art art?" And I loved that it was asked so intelligently and eloquently. I had the letter for several weeks, maybe even months, before I knew exactly what to do with it. I had to spend time with it. First I thought it was about finding the person who wrote it. Did you?

Yes, I found him. He was incredibly nice. He told me it wasn't answered and that he remembered waiting for months for the response. No one ever wrote back. And so there was this open question held within an object that had waited for a reply for forty years, which also happened to be my exact age at the time. I really love that space that was created by a question being asked and not answered yet. You're making a cut in time, like a film editor. Yeah, exactly. A question asked forty-one years ago is answered by 179 people, forty-one years later. It's just beautiful to me, because it sort of points at everything that's changed, but indirectly. Are there teachers or other artists who have been mentors to you? In college, I loved the work of Mark Dion and Jimmie Durham. I wrote to them both, kind of like a fan letter: "I love you. Please can I be your assistant for free for a month?" And they both wrote back and said yes, which was unbelievable. So I got to work with both of them, and that was huge. How old were you then? Maybe nineteen or twenty. I was already at art school. That was an enormous step, just seeing how accessible they were and then getting to travel with them. I lived in Berlin with Jimmie for a month, and I ended up working for Mark for a long time, and then we'd travel around Germany. I got an inside view of the life of an artist. The older I get the more I realize how important it was. Just having a real sense of what that life could be like. I grew up in rural Cornwall, and I had very little exposure to art as a kid. It wasn't part of our family life or anything. In middle school, we would do art classes and it would be like, draw a pencil drawing of Salvador Dalí paintings. It was that type of art. I was really into it; I thought that was what art was. And then, when I was fourteen or fifteen, I found a café in my town where I would go, and the people who ran the café were really into mail art and Fluxus, which felt so random, I can't tell you. It would be as if you found it in Antarctica under a stone. For some reason they would show me this stuff and talk to me about mail art. I thought that was extraordinary. I was just like, "Oh, God. This is it." The idea that this can be art.

Paula Kupfer is an art historian and editor based in Pittsburgh.